(English)

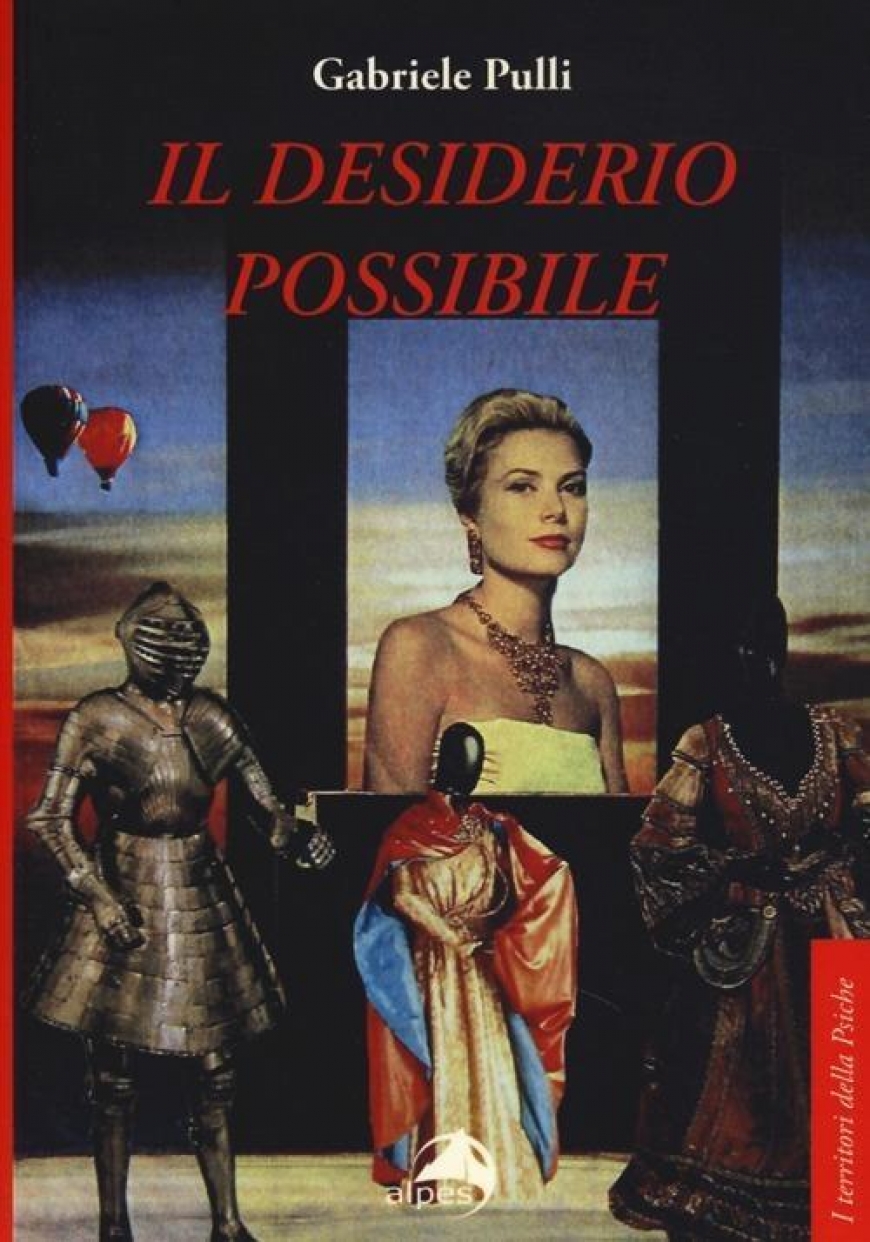

Gabriele Pulli

Il desiderio possibile

Alpes Italia s.r.l., Roma 2013

They seem contradictory, the desire for something (which is extinguished by possessing it, or - but only according to Freud - by the failure to satisfy it) and the desire to desire, which seems never-ending. In reality, one can see them ‘in a much more intimate relationship’, if one thinks of how desire can survive both by being satisfied - if the desire for something continues to be a desire for something desired, while being satisfied - and not being satisfied, if the unfulfilled desire survives as a desire to desire.

The book, at least in the first part, seems to be inspired by a movement of thought reminiscent of that of the relationship between Eleatism, with the absolute opposition being-nothing, and its overcoming, when Plato introduces the negative, which is necessary and implicit in the affirmation of being, into the positive. It is a character of Gabriele Pulli's writings, which he has used (if one may say so), this dialogue with the greatest thoughts of all time, but in his own way: that is to say, it is necessary, even in this case, to bring the discourse back to the domains of the psyche, meaning that the concepts at stake here refer to the domain of the mind, as it is thought of at the crossroads of philosophy, the sciences of man, and psychoanalysis.

The discussion on desire is conducted starting from the way it is understood in J.P. Sartre's Being and Nothingness in which ‘satisfied thirst’ is not made to coincide with ‘suppression of thirst’: desire is defined by the French thinker as ‘an emptiness that is filled, but gives form to that which fills it’. If water gives the full, the full will be ‘enveloped in an emptiness that remains and imposes its own form on it’ (1). Desire is thought of as an empty nothingness; but this emptiness is indispensable to consciousness, as characterised by being ‘for itself’, by the distance of itself from itself (thus different from any other being that is ‘in itself’, is fully adequate to itself). This emptiness, non-being or nothingness, constitutive of consciousness, allows it its character, which consists, together, in the fact that ‘it is what it is not, and it is not what it is’ (Sartre, cit. p. 3): being itself, in the case of consciousness, lies in its perennial displacement with respect to itself.

This then appears to be the version, applied to the definition of consciousness, of the Platonic dialectic of being and nothingness: consciousness ‘never coincides with itself’ (4). Desire is ‘human fact’ because human reality is ‘lack’ and such it remains is that striving for a surpassing that is never coincident with itself, nor can be, which is expressed in the Hegelian unhappy consciousness.

In the chapter on desire and fulfilment, the author discusses the relationship, in Sartre, between unfulfillability and fulfilment of desire, which he tries to explain through the function/position of nothingness ‘in’ consciousness (9). If the constitutive condition of consciousness as ‘for itself’ is that, it has been said, in it is ‘pure nothingness’, and yet consciousness as the fulfilment of desire is capable of ‘containing the pure being of being-in-itself (the “something”), therefore of giving it its own form’ (10), the coexistence, with fulfilment, of the unfulfillability of desire can be explained by the fact that pure nothingness exercises in consciousness ‘its own function in an unconscious way’ (ibid.). Precisely because the unconscious intuits the nothingness that eludes consciousness, ‘it becomes possible for human reality (...) to contain the absolute being of the in-itself, to reach it without losing its own nature, but affirming it’ (12-13), and the desired object is ‘desirable... insofar as it is enveloped ... as if by a veil “made” of nothingness’ (13).

This is followed by the parts on desire and lack, desire and recognition, desire and pain.

In the analysis of the difference between ‘love fantasy’ and ‘idealisation of the beloved object’, the meaning of the difference between a desire that, not coinciding with any ‘reality’, remains a desire to desire, and ‘is fulfilled by the mere fact of existing’ (19) and desire for something, of which the former, however, remains, ‘is the condition of possibility of fulfilment’ (17, 19): if the former were not, neither would the latter be.

The author thus deals with desire and recognition, understanding the latter in the Hegelian sense of the desire for recognition (dialectic of self-consciousness) by the other, and the relationship between the desire to desire, the desire for recognition and the desire for the object.

Finally, speaking of the relationship between desire and pain, the sense of the intraconscious presence of nothingness is examined, in the perception of pain and therefore of lack as the source of pain: ‘the relationship between the nothingness that causes pain and the nothingness that makes things desirable is thus understood’ (30): if the nothingness present in pain has been elaborated, then it becomes ‘the veil that, enveloping things, makes them desirable’ (ibid.).

The conclusion of this part and of the book, after analysing with his usual sharpness the difference between the first and subsequent satisfactions of a need, identifies it not only in nostalgia (34), but also in the absolute uniqueness of the first time (35), which one is then induced to seek, without there being any, in subsequent times.

It helps the pain of loss, in the case, that ‘the atmosphere proper to the memory and at the same time to the object of desire’ can also be the result of an elaboration ‘of the pain of the non-existence of things’ (37): only in the persuasion that each moment, while in some way repeating the past, is at the same time ‘history in itself’ and therefore encounters ‘something wrapped in the nothingness of not having been, as well as the nothingness of no longer being’ (37). The nothingness of grief has been worked out.

Everyone draws his or her own conclusions, not least because of the fertile relationship of this highly imaginative conceptuality between poetry and thought: being able ‘to find the new in the heart of the past, and the past in the heart of the new’ (38).