Corpo, immagine ed emozione nella creazione del mondo. (Italiano, inglese)

Recensione a: Rubina Giorgi, Jakob Böhme. Il corpo in Dio e nell’uomo.

La finestra editrice, Lavis (TN), 2017

“In grado di parlare al lettore d’oggi” (sono le) dottrine

böhmiane dell’immagine e dell’immaginare, nonché della

corporeità e del corpo” (R. Giorgi, op. cit, p.102)

"Qui Spinoza … sta dicendo che l’idea di un oggetto non può manifestarsi in una data mente in assenza del corpo …

Niente corpo, niente mente"

(A. Damasio, Alla ricerca di Spinoza, 255)

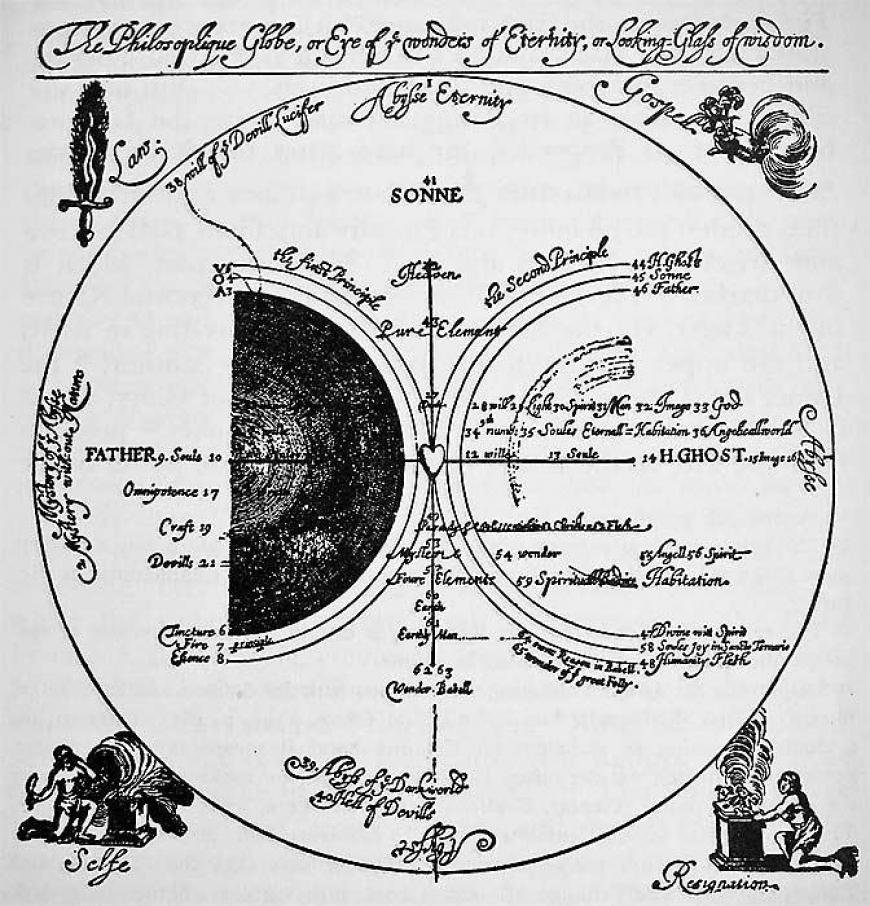

Dopo essersi interessata a lungo, anche nell’insegnamento universitario, al pensiero del mistico e filosofo del Seicento Jakob Böhme – si veda Alla ricerca delle nascite, ed. La Nuova Foglio, Pollenza (Mc) – , Rubina Giorgi è tornata, negli ultimi anni, a quella molteplice grande impervietà, per disegnarvi, pur avendo presente la più aggiornata ricerca storiografica, proprie interpretazioni, inusitati passaggi.

Intanto occorre constatare la scarsa presenza di lavori su Böhme in Italia rispetto agli altri paesi europei, nei quali le edizioni delle opere e la bibliografia sul teosofo tedesco sono prosperate a partire dal Seicento e dalle correnti mistico-pietiste del Settecento, all’epoca romantica ottocentesca e fino alle edizioni del Novecento.

Il pensiero di Böhme appare intriso di un’esigenza traducibile in politica, che i suoi contemporanei inglesi, coinvolti in quel disegno per molti aspetti affine, seppero intendere come a favore del liberalismo se non della democrazia, riservando dunque a quell'aspetto, più ancora che alla sua mistica e teosofia, favorevole accoglienza. Questo è detto con chiarezza nel saggio di Rubina Giorgi, allorché vi si spiega la fortuna o l’importanza di Böhme “fino alla metà del Novecento” (p. 34), precisando, appunto, il tema della libertà che attrasse i posteri e che ricorda la grande figura di Giordano Bruno; e si comprende allora la congettura che ci viene proposta, circa una diversa nostra sorte, che noi avremmo conosciuto, qualora “l’attitudine teosofico-iniziatica dello sparso böhmismo europeo, insieme ad altri filoni iniziatici della Qabbalah cristiana e della mistica islamica presenti in Europa, si fossero consolidati”.(p. 34)

A prescindere dalle interpretazioni politiche del pensiero di Böhme, e più in generale, in che modo si può vedere nella rappresentazione böhmiana del mondo una discussione problematica che investe anche noi lettori del nostro tempo? Come si risponde alla domanda su “come Böhme ci abbia, in qualche senso, anticipati” (p. 10) e com’è possibile che anche un lettore attuale possa riconoscere in quel pensiero qualcosa di “persino bruciante per il suo oggi”? (p. 10).

Questa domanda pone il libro; per rispondere è necessario conoscere almeno qualche riferimento di pensiero dell'autore tedesco.

Come viene descritto, nel pensiero di Böhme, il passaggio dal nulla all’essere?

Il mondo dei molti e delle differenze, che implica la domanda sul come il mondo possa essere, trova qui in Böhme il presupposto nel fatto che il nulla-origine desideri conoscere se stesso, e pone in atto una strategia a tal fine: è l’improbabile presupposto, di certo inusuale per il lettore che non sappia di filosofia e teologia, per cui “con suprema contraddizione” (p. 38) “l’Ungrund“, il “senza fondamento e se vogliamo l’impensabile niente o, col suo vero nome (che tuttavia vira concettualmente, rispetto al “senza fondamento”, e sarà quindi adesso “der Wille”, “è movimento che vuole e desidera”, desidera “Contemplarsi e manifestarsi”(p. 38): la creazione è dunque specchio aperto all’occhio (dell'infondato nulla, l'Ungrund) che desidera.

Resta aperta la domanda sull’appartenenza “di” quell’occhio. Come può l'infondato nulla essere anche Wille, e dunque volontà desiderante, e farsi occhio che "si" vede?

Ciò detto, la brama (Wille) produce “per un verso Dio” e peraltro “il vedere, che è l’immaginazione” e “l’intera architettura böhmiana” è un frutto non della ragione ma “dell’intelletto intuitivo… ossia dell’immaginazione”(p. 42).

Sembra, questo, il cuore dell’interpretazione del libro: Rubina Giorgi nota puntualmente che si tratta di un momento importante per la storia del nostro modo di pensare. La strada per un modo di immaginare la fondazione dell’essere e dell’esistere stesso per noi si trova qui, è tracciata.

Ma come sarà possibile tradurre quel pensiero nelle linee della conoscenza odierna, che ancora domanda su come sia possibile per noi un mondo?

La risposta è data nel senso che “da Böhme in poi, e fino a noi, ciò che il senso comune chiama ‘realtà’ sarà legato con insistenti fili sotterranei, per lo scienziato e il filosofo, e in primis forse per il poeta, all’immagine e all’immaginazione”(p. 42).

Per Böhme non v’è difatti realtà senza immagine. Dovrei anche aggiungere: “anche” per noi: dunque questo nostro modo d'intendere è dovuto a lui, agli effetti del suo pensiero?

Pertanto le immagini devono, in qualche modo, essere alle radici stesse della creazione, e, come le idee platoniche sembrano preesistere a quella, così le immagini sono prima e insieme al creato, che non sarebbe concepibile senza di esse, e quindi “tutte le cose sono venute all’esistenza attraverso l’immaginazione divina” (p. 45).

Sembra di dover aggiungere che oggi, attraverso Platone e poi Giambattista Vico, il tema della importanza decisiva delle immagini perché noi abbiamo un mondo giunge nell’attualità attraverso opere ambiziose, attraverso tanti, tra cui il quasi dimenticato Melandri, e della più diversa matrice filosofica, come p. e. Superfici ed essenze (…) di Hofstädter e Sander.

Ma altrettanto importante che il motivo delle immagini, in Böhme, è quello del corpo, è detto in epigrafe come nel titolo, e i due temi stanno insieme. Come viene pensato il concetto del corpo?

Lo si può mediare attraverso i temi delle incessanti nascite e delle Qualità.

Alla base della kinesis, del pulsare “incessante ed eterno” (p. 45), sta la visione per cui “ciò che vive … è in permanenza nascita e nascere” (p. 46): quindi insieme al movimento della forza scatenata (Kraft), per cui “l’affermazione della vita non riesce senza lotta”, affinché visione vi sia, deve darsi un arresto, altrimenti non si vedrebbe alcunché; arresto sia pur parziale, funzionale alla creazione, quindi al nascere del qualcosa che appare in vece dell’informe nulla (p. 61). In conseguenza delle qualità di cui diffusamente si parla, soprattutto nel c. IV, le immagini sono la condizione per l’esistenza delle cose. Ab origine, le Qualità sono le stesse Forme (cfr. p. 54). Si tratta di intendere sotto questo aspetto il tema della natura o tema “delle forme o natura naturans divina” (p. 46).

Non solo immagine e cosa ma anche immagine, parola e cosa, sono insieme. Intendere questo sembra decisivo.

Ciò può essere in quanto in Dio la parola e la cosa sono unite nell’atto creativo, sicché in Dio pensare parola e creare sono tutt’uno: e il pensare avviene inoltre, anche in Dio, intuitivamente o per immagini, ma il punto è che le immagini-parola in Dio danno corpo. La natura verbante divina è ipso facto natura creante divina: e peraltro “Senza corpo, (il che è anche dire: dal momento che un corpo ha sempre forma) senza le forme o Gestalten, Dio non genera la natura” (p. 47) e “il Wesen aller Wesen (essenza di tutte le essenze) in Böhme complessivamente significa Dio e anche la Corporeità” (p. 51).

Non vi sono immagini-parola senza corpo, né può darsi corpo che non sia verbato e perciò immaginato.

Un creare verbante, dunque, o una creazione nel verbo, qualcosa di simile all’apertura del quarto Vangelo; ma, insieme, senza che si possa scindere, ecco comparire l’altro motivo, a fianco dell’immagine, quello del corpo e della corporeità, perché i due sono unum atque idem, lo stesso. Quella di Böhme, l’autrice ribadisce, è insieme “fisica e metafisica” ovvero complessa onto-cosmologia (p. 61). Un corpo per esser tale ha sempre forma o immagine suscettibile di resa in parola e in questo senso si direbbe che “ogni cosa ha una sua bocca per la propria rivelazione” (51).

Così il tema delle immagini comporta quello della creazione. Si direbbe che Jakob Böhme e Antonio Damasio, il filosofo mistico di quattro secoli fa e il neuroscienziato contemporaneo, ponendosi in modo problematico il problema dell’essere delle cose, abbiano incontrato, in modo e prospettiva così diversa, il medesimo tema dell’immagine, anch’essa problema, anzi problema dei problemi.

E le qualità? Insieme al tema delle immagini, è sempre presente quello delle qualità delle immagini. Cosa s'intende? Damasio e i neuroscienziati direbbero: il problema dei qualia. Ma con ciò siamo in ambito di neuroscienze contemporanee.

Anche Damasio come Böhme, trattando il tema dell’immagine e della sua importanza, s’imbatte nel problema dei qualia, che sono le qualità delle cose, i colori o sentimenti che le accompagnano all’atto in cui esse si danno in immagine all’anima, o mente, o coscienza. Queste restano un enigma per Damasio: come sono possibili i qualia?

Il problema delle qualità nel pensiero di Böhme addirittura diviene, di nuovo, il problema della creazione delle cose, dell’universo.

Con ciò si sarebbe dunque già trovato, seguendo il filo del libro di Rubina Giorgi, i motivi dell’attualità di Böhme: il tema delle immagini come fulcro della conoscenza e il motivo del loro apparire sempre congiunte a una qualità. Cioè a un sentimento, più o meno significativo.

Come è evidente nel percorso, gli elementi presenti nel titolo non sono per nulla dati acquisiti ma immagine, corpo, dio e uomo vanno assunti in modo problematico.

Di più – credo che tutto ciò non possa andare separato dal concetto böhmiano della signatura. Che senso ha, nel contesto del mondo, la consistenza vivente delle creature? Ha questo senso, di nuovo: di Parola o immagine divina. Böhme riporta tutto ciò che si vede, si muove, o quella stessa necessità che l’uomo avverte “di essere esposto alla luce dello spirito” (p. 73) che è poi una forza di "creazione seconda" (essendo la "creazione prima" quella divina) nell’uomo, al Fiat, all’originario proferire Parola, come soffio, alito di Spirito divino. Tutto ciò che diciamo essere in atto è “segnatura … del movimento dell’origine” (p. 80).

Segnatura è comunque processo, movimento: essa è

“designazione delle cose, o figura esterna delle cose, attraverso la quale si manifesta la loro vita interna. … Un percorso che passa dal segno, o significante, delle cose alla loro forma visiva (Gestalt), tuttavia procedente verso l’interno, che dunque, per essenza, s’innesta nella sostanza del corpo, trovando (ritrovando) infine approdo nella Wesenheit, settima delle Gestalten o forme: la corporeità” (pp. 80-1).

Signatura: esterno è figura dell’interno.

Anche parola è corpo, corporeità che esprime e media l’interno verso l’esterno, e l’interno, come il primigenio Nulla, deve venire espresso all’esterno, perché “Tutto l’esterno mondo visibile … è una denotazione … o figura … dell’interno mondo spirituale” (p. 82); di qui all’ istanza del circolo, così presente in alcuni motivi del pensiero, non v’è differenza – “si dovrà ritenere che la traiettoria fra interno ed esterno sia non solo continua ma anche circolare” (p. 83).

Forse a questo punto s’intende meglio in che senso l’essenza dell’anima s’indossi come corpo, e il concetto della segnatura avrà carattere ambivalente, fisico e spirituale, insieme; essa è “disvelamento dello spirito nascosto nella carne” (p. 87). Forse la biologia è fondata in Dio stesso (cfr. 88) e parlare del nostro corpo è parlare del corpo di Dio in natura, senza che perciò possa parlarsi di panteismo (cfr. p. 89).

Alla luce degli ultimi studi dell’autrice, alla convergenza tra filosofia e mistica, biologia e neuroscienze, convocando Böhme anche perché egli stesso in termini simili vi perviene, è conseguente che si chiami in causa il cervello. La visione del libro in proposito è che l’ammirazione di Jakob Böhme per le straordinarie qualità o forme o essenze teocosmiche è da ritenersi, sebbene in gran parte inconsapevole, come diretta alle meraviglie del corpo e specificamente del cervello. E qui, ancora, a partire dal riferimento alla ricerche sul corpo umano nella scienza seicentesca, avviene l’innesto dell’importanza delle immagini, e quindi dell’immaginazione, nella nostra modernità.

Qualcosa che maggiormente, nell’ambito della corporeità, richiama il divino universo e la sua vicenda incessante, è appunto questo movimento vivente e mirabilmente complesso del corpo, e del cervello, non solo legato al divino, in quanto corpo, ma anche poiché Dio nasce e di continuo mutando rinasce: il moto vitale è analogo di Dio nell’uomo e nel mondo in quanto creativo/creatore di se stesso e perciò nella modalità del continuo metamorfosare (cfr. pp. 90, 93); per tale motivo, la scienza ne deve rincorrere la natura, perché esso è l’esempio del perenne moto dell’universo (cfr. 94-6).

“… tutte le forze vanno dalla testa e dal cervello nel corpo e nelle vene sorgive … della carne… nella testa o nel cervello dell’uomo tutte le forze sono miti e piene di gioia… tutte le forze vanno dal cervello nel corpo e in tutto l’uomo” (Aurora, cit. a pp. 90-1).

Body, image and emotion in the creation of the world.

Reviewed in: Rubina Giorgi, Jakob Böhme. Il corpo in dio e nell’uomo.

La finestra editrice, Lavis (TN) ,2017

Able to speak to today's reader (are the)

Böhmian doctrines of image and imagining, as well as of the

corporeality and the body (R. Giorgi, op. cit, p.102)

Here Spinoza ... is saying that the idea of an object cannot manifest itself in a given mind in the absence of the body ...

No body, no mind.

(A. Damasio, In Looking for Spinoza, tr. it. Milano, p. 255)

After having been interested for a long time, also in university teaching, in the thought of the seventeenth-century mystic and philosopher Jakob Böhme - see Alla ricerca delle nascite (lingua e mania), ed. La Nuova Foglio, Pollenza (Mc) - , Rubina Giorgi has returned, in recent years, to that many great imperviousness, to draw her own interpretations, unusual passages, while keeping in mind the most up-to-date historiographical research.

In the meantime, it is necessary to note the paucity of works on Böhme in Italy compared to other European countries, in which editions of works and bibliography on the German theosophist have thrived from the seventeenth century and the mystic-pietist currents of the eighteenth century, to the nineteenth-century Romantic era and up to twentieth-century editions.

Böhme's thought appears imbued with a need that can be translated into politics, which his English contemporaries, involved in that related design in many ways, were able to understand as being in favor of liberalism if not democracy, thus reserving for that aspect, even more than for his mysticism and theosophy, favorable reception. This is made clear in Rubina Giorgi's essay, when there she explains Böhme's fortune or importance "until the middle of the twentieth century" (p. 34), specifying, precisely, the theme of freedom that attracted posterity and that recalls the great figure of Giordano Bruno; and one can then understand the conjecture that is proposed, about a different fate of ours, which we would have known, if "the theosophical-initiative attitude of the scattered European Böhmism, together with other initiatory strands of Christian Qabbalah and Islamic mysticism present in Europe, had been consolidated" (p. 34).

Regardless of the political interpretations of Böhme's thought, and more generally, how can we see in the Böhmian representation of the world a problematic discussion that also invests us readers of our time? How does one answer the question of "how Böhme has, in some sense, anticipated us" (p. 10) and how is it possible that even a present-day reader can recognize in that thought something "even burning for his or her today"? (p. 10).

This question poses the book; to answer it, it is necessary to know at least some reference of the German author's thought.

How is the transition from nothingness to being described in Böhme's thought?

The world of the many and of differences, which implies the question of how the world can be, finds its presupposition here in Böhme in the fact that the nothing-origin desires to know itself, and sets up a strategy to that end: it is the improbable presupposition, certainly unusual for the reader who does not know about philosophy and theology, whereby "with supreme contradiction" (p. 38) "the Ungrund," the "groundless and if you will the unthinkable nothingness or, by its real name (which nevertheless veers conceptually, with respect to the "groundlessness," and will thus now be "der Wille," "is movement that wills and desires," desires "to contemplate and manifest itself"(p. 38): creation is thus an open mirror to the eye (of the groundless nothingness, the Ungrund) that desires.

The question about the belonging "of" that eye remains open. How can the unfounded nothingness also be Wille, and thus desiring will, and become the eye that "sees" itself?

That said, the longing (Wille) produces "in one respect God" and moreover "the seeing, which is the imagination" and "the whole Böhmian architecture" is a fruit not of reason but "of the intuitive intellect... that is, of the imagination"(p. 42).

This, it seems, is at the heart of the book's interpretation: Rubina Giorgi punctually notes that this is an important moment in the history of our way of thinking. The road to a way of imagining the foundation of being and of existence itself for us lies here, is laid out.

But how will it be possible to translate that thought into the lines of today's knowledge, which still questions how a world is possible for us?

The answer is given in the sense that "from Böhme onward, and up to us, what common sense calls 'reality' will be linked with insistent subterranean threads, for the scientist and the philosopher, and primarily perhaps for the poet, to image and imagination"(p. 42).

For Böhme there is in fact no reality without image. I should also add: "also" for us: so is this way of our understanding due to him, to the effects of his thinking?

Therefore images must, in some way, be at the very roots of creation, and, just as Platonic ideas seem to pre-exist that, so images are before and together with creation, which would not be conceivable without them, and therefore "all things came into existence through the divine imagination" (p. 45).

It seems to be necessary to add that today, through Plato and then Giambattista Vico, the theme of the decisive importance of images for us to have a world comes into actuality through ambitious works, through so many, including the almost forgotten Melandri, and of the most diverse philosophical matrix, such as e. g. Surfaces and Essences (...) by Hofstädter and Sander.

But just as important that the motif of images, in Böhme, is that of the body, is said in the epigraph as in the title, and the two themes stand together. How is the concept of the body thought of?

It can be mediated through the themes of incessant births and Qualities.

Underlying the kinesis, the "ceaseless and eternal" pulsing (p. 45), is the vision whereby "what lives ... is permanently birth and being born" (p. 46): thus together with the movement of unleashed force (Kraft), whereby "the affirmation of life fails without struggle," in order for there to be vision, there must be a halt, otherwise nothing would be seen; a halt, albeit partial, functional to creation, thus to the coming into being of the something that appears in place of the formless nothing (p. 61). As a result of the Qualities discussed at length, especially in c. IV, images are the condition for the existence of things. Ab origine, the Qualities are the Forms themselves (cf. p. 54). It is a matter of understanding in this respect the theme of nature or theme "of forms or natura naturans divina" (p. 46).

Not only image and thing but also image, word and thing, are together. Understanding this seems decisive.

This may be inasmuch as in God word and thing are united in the creative act, so that in God thinking word and creating are one: and thinking takes place moreover, also in God, intuitively or by images, but the point is that word-images in God give body. The divine verbal nature is ipso facto divine creating nature: and moreover, "Without body, (which is also to say: since a body always has form) without forms or Gestalten, God does not generate nature" (p. 47) and "the Wesen aller Wesen (essence of all essences) in Böhme altogether means God and also Corporeality" (p. 51).

There are no word-images without a body, nor can there be a body that is not verbal and therefore imagined.

A verbal creation, then, or a creation in the verb, something similar to the opening of the Fourth Gospel; but, together, without being able to be split off, here appears the other motif, alongside the image, that of body and corporeity, for the two are unum atque idem, the same. Böhme's, the author reiterates, is both "physical and metaphysical" that is, complex onto-cosmology (p. 61). A body to be such always has form or image susceptible to rendering into words, and in this sense one would say that "everything has its own mouth for its own revelation" (51).

Thus the theme of images involves that of creation. One would say that Jakob Böhme and Antonio Damasio, the mystical philosopher of four centuries ago and the contemporary neuroscientist, problematically posing the problem of the being of things, encountered, in such a different way and perspective, the same theme of image, also a problem, indeed a problem of problems.

What about qualities? Along with the theme of images, there is always that of the qualities of images. What is meant by this? Damasio and neuroscientists would say: the problem of qualia. But with that we are in the realm of contemporary neuroscience.

Also Damasio like Böhme, in dealing with the subject of image and its importance, runs into the problem of qualia, which are the qualities of things, the colors or feelings that accompany them at the act in which they are given in image to the soul, or mind, or consciousness. These remain an enigma for Damasio: how are qualia possible?

The problem of qualia in Böhme's thought even becomes, again, the problem of the creation of things, of the universe.

With this one would therefore have already found, following the thread of Rubina Giorgi's book, the reasons for Böhme's topicality: the theme of images as the focus of knowledge and the reason for their always appearing conjoined to a qualia. That is, to a feeling, more or less significant.

As is evident in the course, the elements in the title are by no means taken-for-granted data but image, body, god and man must be taken problematically.

More - I believe that all this cannot be separated from the Böhmian concept of signature. What sense does the living consistency of creatures make in the context of the world? It has this sense, again: of Word or divine image. Böhme brings everything that is seen, moves, or that very need that man feels "to be exposed to the light of the spirit" (p. 73) which is then a force of "second creation" (the "first creation" being the divine one) in man, back to the Fiat, to the original utterance of Word, as breath, breath of divine Spirit. Everything we say to be in act is "marking ... of the movement of the origin" (p. 80).

Signature is, however, process, movement: it is

"designation of things, or external figure of things, through which their internal life is manifested. ... A path from the sign, or signifier, of things to their visual form (Gestalt), nevertheless proceeding inward, which therefore, by essence, is grafted into the substance of the body, finding (rediscovering) finally landing in the Wesenheit, seventh of the Gestalten or forms: corporeality" (pp. 80-1).

Signature: exterior is a figure of interior.

Word is also body, corporeity expressing and mediating the inside to the outside, and the inside, like the primal Nothingness, must come to be expressed on the outside, for "The whole external visible world ... is a denotation ... or figure ... of the internal spiritual world" (p. 82); hence to the 'instance of the circle, so present in some motifs of thought, there is no difference-"it will have to be assumed that the trajectory between inside and outside is not only continuous but also circular" (p. 83).

Perhaps at this point it is better understood in what sense the essence of the soul wears itself as a body, and the concept of the marking will have an ambivalent character, physical and spiritual, together; it is "unveiling of the spirit hidden in the flesh" (p. 87). Perhaps biology is grounded in God himself (cf. 88), and to speak of our body is to speak of God's body in nature, without therefore being able to speak of pantheism (cf. p. 89).

In light of the author's latest studies, at the convergence of philosophy and mysticism, biology and neuroscience, summoning Böhme also because he himself in similar terms comes to it, it is consequent that the brain is called into question. The book's view in this regard is that Jakob Böhme's admiration for extraordinary theocosmic qualities or forms or essences is to be seen, albeit largely unconsciously, as directed to the wonders of the body and specifically the brain. And here, again, beginning with the reference to research on the human body in seventeenth-century science, is the grafting of the importance of images, and thus imagination, in our modernity.

Something that most, in the sphere of corporeality, recalls the divine universe and its incessant vicissitude, is precisely this living and admirably complex movement of the body, and of the brain, not only related to the divine, as a body, but also because God is born and continually changing by being reborn: the vital motion is analogous to God in man and in the world as creative/creator of himself and therefore in the mode of continual metamorphosis (cf. pp. 90, 93); for this reason, science must chase its nature, for it exemplifies the perennial motion of the universe (cf. 94-6).

"... all the forces go from the head and brain into the body and into the spring veins ... of the flesh ... in the head or brain of man all the forces are mild and full of joy ... all the forces go from the brain into the body and into the whole man" (Aurora, cited at pp. 90-1).

Nocera Inferiore, 2018-2023 Carlo Di Legge